We know the names of labor activists Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, but do you know the legacy of Maria Moreno? Moreno was the first woman farmworker to be hired in America as a union organizer. Her momentous accomplishments were almost lost to time, remembered only by those who were there, but that changed when director Laurie Coyle heard her story.

In the 2019 PBS program “VOCES: Adios Amor: The Search for Maria Moreno,” Coyle ensures Moreno’s story continues on for future generations. We interviewed director Laurie Coyle to celebrate Maria Moreno and the documentary “Adios Amor,” for Women’s History Month.

While working on the Cesar Chavez documentary, “The Fight in the Fields,” directed by Rick Tejada-Flores and Ray Telles, you came across photos taken by George Ballis, a photographer and part-time farmworker organizer. The photos were of Maria Moreno, then unknown to you. What inspired you to not only learn her story, but to also create a documentary about her?

The photographs inspired me: there were hundreds of stunning black & white images full of poetry and emotion. I might not have known what the story was, but they were telling a powerful story. Women have been powerful forces in social justice movements, but their contributions have rarely been documented, especially if they are migrant mothers. George Ballis was known for taking many of the most famous photos of Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers movement, but the Maria Moreno photographs had never been published.

Archival research is always a treasure hunt, but there’s a special serendipity in finding someone you weren’t looking for—in this case Maria Moreno. Even if nobody knew who she was, she wasn’t anonymous. She was center stage. She had charisma. I had grown up in a big family, so I really appreciated the pictures of Maria organizing with her children at her side. Beyond the speeches and picket lines, Ballis photographed her at home, cooking, chopping wood, getting the kids ready for school, sleeping in the back of the car. She was a woman of her time, an indigenous Mexican American woman rockin’ it in her high heels and long hair braided in beautiful plaits – not to mention her rubber boots, flannel shirts and safari helmet. She looked straight into the camera and grabbed you by the throat!

As a female filmmaker who’d been hired to work on many documentaries about illustrious men, I sensed that Maria was the “shero” I’d been looking for. Although it was years before I started this film project, I never ever forgot the beautiful photographs and their mysterious protagonist.

The storyline of the film includes your personal search for Moreno, would you say this was a structural or stylistic choice, or both?

I would say both! I started filming at the same time as I started searching for Maria. I had no idea where that would land me, and there was a good chance that I was going to end up with a 15-minute experimental documentary about “the woman who got away.” In retrospect, not finding out what had happened to Maria would have been a huge letdown. Meeting her family and colleagues brought Maria to life as a three-dimensional person. Filming them return to their youth and share their memories and collections of movies, memorabilia and recordings made this film their story too.

It was never my aspiration to be in front of the camera, but my accidental discovery of Maria and my subsequent search felt like essential parts of Maria’s story. I have always wanted to inspire viewers to launch their own journeys of discovery. Beyond search engines, on the ground research is a real adventure and it’s fun.

Interweaving my search with Maria’s unfolding story was a structural challenge. If you start off with a search, you conclude with the search or its results, right? But once I met Maria’s family, I had to break the narrative rules and “pass the baton.” ADIOS AMOR starts with my search, but at the end of the day it’s Maria Moreno’s journey and her story.

There are many different themes that come through in the film. How did you decide to balance them all while also telling Moreno’s story?

Every filmmaker has got enough material to write a book, but if you don’t telescope that into a cohesive narrative the whole thing collapses. Every single frame is a choice, so there were lots of tough choices. But with a life as vibrant and complex as Maria Moreno’s, the themes emerged organically from her story. Memory, motherhood, migration, farm labor, the role of faith in social activism, the power of photography to bear witness to injustice, all came into play. The more personal and heartfelt a story is, the more deeply the themes resonate. I’m fascinated by how Maria’s story resonates differently with different audiences, how viewers zero in on one theme or another. Who out there grew up in the desert next to a water tank? At the same time, who wouldn’t give anything to revisit their childhoods? Folks relate to ADIOS AMOR on an emotional level, whatever their life circumstances have been. I have to add that Chicano audiences really get the humor in ADIOS AMOR, while white audiences are usually super serious.

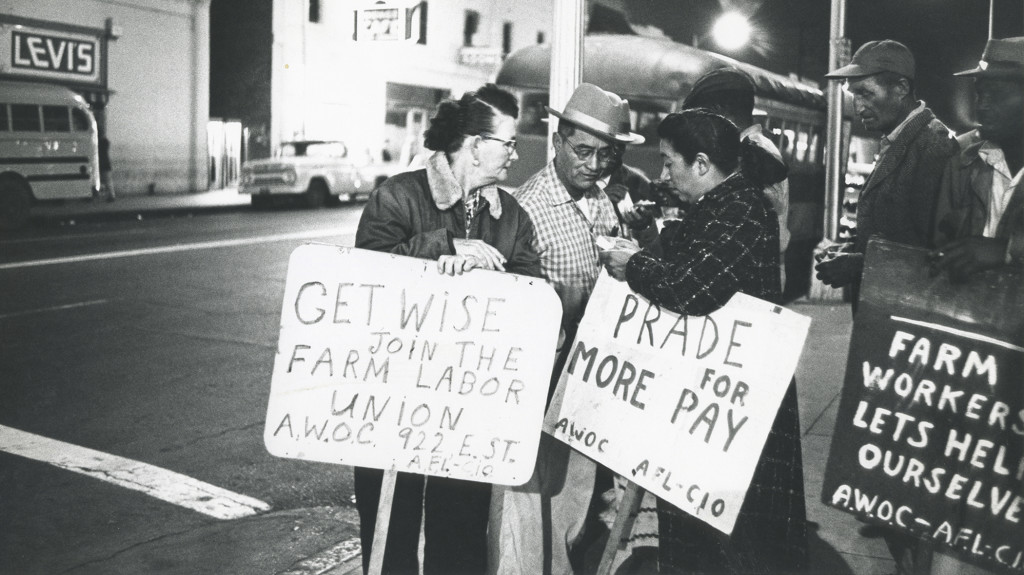

Maria on the AWOC picket line with farmworkers in Fresno 1961. Credit: © 1978 George Ballis/Take Stock

The film required a significant amount of research. How did you decide on where to begin and was the finding of her audio recordings the major breakthrough for the film?

I began with a visit to George Ballis, the photographer. He had just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and they’d given him two months to live. He was weak but told me, “let’s go for it,” so I headed down with my crew to the Sierra foothills where he lived with his wife Maia. Since he got tired quickly we spread the interview over two days, but I came away with enough inspiration to fuel the rest of production and George lived for another ten months!

In Berkeley I was blessed to meet Henry Anderson, Maria’s fellow union organizer, whose attic was a treasure trove. Henry’s encyclopedic recall of events that had transpired sixty years ago was even more remarkable than his archive. I discovered things about Maria’s work as a union organizer that her own family didn’t know, such as Ernesto Galarza’s exposé about the banned documentary Poverty in the Valley of Plenty that led to Maria and other AWOC leaders being sued.

I had been in production for almost a year before I made contact with Maria Moreno’s family. I was three years into production before I found the audio recordings. I had a complete rough cut before the Moreno’s found their 8mm home movies. So the discoveries continued up to the end. You’re right that finding the recordings of Maria was a game changer. Everybody talked about what a powerful orator she was, but the recordings had gone missing thirty years before and I was trying to figure out how to tell the story without them. Hearing Maria tell her own story changed everything, and I feel so much gratitude to Ernest Lowe and KPFA radio for making these recordings.

In 1958, a huge flood in Woodlake, CA left thousands of farmworkers hungry and without work. Moreno used her voice to fight and convince relief agencies to offer assistance to the starving farmworkers. This brought her to the attention of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) who soon hired her on as an organizer. What characteristics do you feel made Moreno a good spokesperson?

Maria spoke from the heart and she told the story of her son going blind from hunger with great emotion. No doubt her childhood experience accompanying her father influenced her. He was an itinerant preacher, and as Martha Moreno says in the film, “he could preach up a good storm.” And Maria could too. Nowadays it’s common for public speakers to share their personal stories to connect with their audiences. Not so in Maria’s time, when labor organizers were more accustomed to speaking in grand terms about social inequities. Maria also had a sense of humor, and that really helped her connect with people from different backgrounds. She had no qualms about confronting people about the injustices facing farmworkers. Being passionate and direct was what led AWOC to choose her as their spokesperson, but ironically that’s what got her into trouble with her union bosses.

Maria poses with her children in Holtville, CA after the family migrated from Texas in 1940. Credit: © 2017 Moreno Family

Moreno was the mother of 12 children and had a loving, supportive husband. We have seen with other activists and labor organizers where their work became the predominant role in their lives, sometimes overshadowing their role in the family. Was this also the case for Moreno? How did her children reflect on this?

An important motto in the farmworkers movement has always been, “organize your family first!” Maria Moreno was a trailblazer in that regard, and it seems that she managed to keep a healthy balance between her union work and family life. At home Maria and her husband Luis would share domestic tasks like cooking and dishwashing. Some of her sons and daughters were already adults while others were still toddlers, so they took care of one another and had their division of labor in place. What made Maria’s situation unique is that she had an identical twin sister who didn’t have her own children, so Aunt Sally and her husband could step in when needed. What working mom wouldn’t love to have a double when she has to be away from home!

One of the most powerful moments in the film occurs after The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) decides to pull the plug on AWOC. To save the union, AWOC selected Moreno as their delegate to AFL-CIO’s national convention with the hopes that she could restore their funding support. She spoke alongside some of the most influential figures in history: John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Eleanor Roosevelt. How do you connect her influential legacy to the knowledge that she is still unknown to many?

It’s troubling that Maria persuaded the AFL-CIO to renew support for AWOC and less than a year later she would effectively be silenced. But we have to remember the times in which she lived. It was the waning years of McCarthyism, before second wave feminism or the March on Washington. At the convention, Martin Luther King Jr. was applauded, but A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was excoriated for calling out the racism in the AFL-CIO. Eleanor Roosevelt was the only woman listed on the convention roster, so Maria Moreno was an afterthought.

It’s significant that Maria was the first female farmworker in the U.S. to be hired as a union organizer. She was an indigenous Mexican American migrant mother with a second grade education and twelve children. She was elected by a multi-ethnic group of Okie, Filipino, Black, Mexican American and Mexican immigrants at a time when California was highly segregated. Her union bosses were older white men who had never done a day of farm labor in their lives.

There’s a meta-historical dynamic at play too: the tendency to embrace one historical narrative as the official story. The United Farm Workers unfortunately played a part in erasing the legacy of earlier farm labor struggles, as if the movement started with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Regrettably I found evidence of their willful forgetting of Maria Moreno. But it’s not just them, we all want to anoint our heroes. I don’t want to displace one famous leader with another. It’s really about embracing history as an ever-evolving dialogue with the past, thinking about whose voices are represented when histories are shaped.

What do you think might have happened if Moreno stayed organizing for the union?

Chances are she would have joined her Filipino brothers when they launched the 1965 grape strike! Although most AWOC members had quit the union after independent-minded organizers like Maria and Henry were fired, the militant Filipinos kept AWOC going, due in large part to the commanding leadership of Larry Itliong. I don’t know how that would have worked out when Chavez’s NFWA joined AWOC’s strike, since Cesar had complained about Maria’s “big mouth” when they worked for (apparently) rival unions. It would be interesting to know whether Dolores Huerta might have seen things differently, since she was close to AWOC in its early days and testified at the Strathmore conference where Maria was elected to represent AWOC at the AFL-CIO convention.

After years of labor work, Moreno followed in her father’s footsteps to become a minister. She traveled between California and Mexico to preach and provide charity to the local communities. She continued to use her voice to help others – what does this tell you of Moreno’s spirit?

Some people think Maria jumped off the deep end when she became a preacher. It must have been a real slap in the face to go from being a beloved spokesperson to being fired without just cause. Maria’s daughter Olivia describes the sudden change as a real existential crisis: like the prophets of old, Maria headed to the desert to wrestle with and reflect on her calling. And like so many people have done, whether crossing a border, sailing an ocean, rebuilding after a fire or flood—she reinvented herself—but on the solid foundation of her faith, family values and commitment to justice.

If you take a step back you can see the continuous thread that runs through her migrant childhood, years as a union organizer, and ministry. Maria insisted on pursuing a path that touched the lives of others. Anti-poverty work is essential, whether or not it leads to structural change. But I still see her departure as a real blow and wonder what she might have contributed if she had remained active in the broader movement for labor and civil rights. Maria’s spirit was indomitable, and her restless spirit hovers over the unfinished work of improving the lives of our nation’s farmworkers.

Vicente Franco films Moreno family members at the site of their former desert home in Arizona. Credit: © 2017 Adios Amor/Laurie Coyle

It seems Moreno’s children have continued her ministry and charity work. Is there a way for the public to look them up and follow this work as well?

Maria’s children have gotten on in years, and the mission that they founded with their mother in San Luis, Mexico, has been taken over by another pastor. They are still active in their local Pentecostal congregations in Texas, Arizona and California. Until recently Lillian served on the board of a migrant health clinic in northern California. Martha has achieved renown as a Gospel singer. The next generations carry on the legacy: granddaughter Lisa Alama lobbied successfully for the Texas legislature to honor her grandmother with an official proclamation; granddaughter Felicia Portugal works as a nurse with incarcerated populations; granddaughter Diana posted her story Echoes of Faith here; and great-grandson Edward Lee Moreno II works for the California Environmental Justice Alliance.

During the making of the film you co-founded MiHistoria, a storytelling initiative dedicated to sharing stories of the Latina experience. Can you share the purpose behind MiHistoria?

When I began searching for Maria, I met many people who said, “I’ve never heard of Maria Moreno, but let me tell you a story about my abuela, tía, madre” etc. There are many “Marias” with remarkable stories and nowadays the tools exist to gather and share them.

ADIOS AMOR’S first grant came from the Creative Work Fund, which supports artists collaborating with community organizations. My partner was the Chicana Latina Foundation, a northern California non-profit that provides scholarships, mentoring and leadership training for Latinas pursuing post-secondary education. Inspired by Maria Moreno and the notion that “we stand on the shoulders of those who came before,” we convened a workshop to tell stories about women who had made a difference in our lives. Every story written and spoken evoked healing, inspiration and action. We sensed the vast potential of untold stories and the transformative power of sharing them.

This pilot project took off a year later when I met storyteller/educator Albertina Zarazúa Padilla. We launched MiHistoria, a collaborative storytelling project that bears witness to the Latina experience, strengthens inter-generational ties, builds bridges of understanding between urban and rural women, and empowers Latinas to become the authors of their own stories. We benefitted greatly from work-shopping the project at the Latino Producers Academy in 2013. MiHistoria continues doing storytelling workshops, including many with farmworker women’s organizations. You can explore these stories at www.mihistoria.net and upload your own story too.

By creating “Adios Amor”, you helped to reshape the history of the farmworkers movement to include one of its earliest fighters. In doing this, you also cemented the role of a pioneering woman within the movement. Do you find it important to carve space for women in your films?

Absolutely. Before I went to film school I worked as an oral historian, recording the stories of the Chicana and Mexicana garment strikers at Farah Manufacturing on the Tex-Mex border. Their walkout, picket lines and boycott were historic, but their personal stories are engraved in my memory. I’m excited about the next stories that will see the light of day.

I always think of Virginia Woolf’s rallying cry at the end of A Room of One’s Own, that Shakespeare had a sister who never wrote a word because she was washing the dishes and putting the children to bed; that she lives on in you and in me. How many Marias walk among us? It’s for us to draw a circle around their stories and invite them to speak.

“Adios Amor” is available for purchase at www.adiosamorfilm.com. Share your own Latina stories with Mi Historia.

About the filmmaker: Laurie Coyle is a documentary filmmaker and writer. Her last film was OROZCO: Man of Fire, which aired on PBS AMERICAN MASTERS and was nominated for the Imagen Award and National Council of La Raza ALMA award. Laurie’s work has been supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, San Francisco Arts Commission and Creative Work Fund, among others. Her writing credits include the PBS specials Speaking in Tongues, The Slanted Screen, Life on Four Strings and The Journey of the Bonesetter’s Daughter-The Making of an Opera. She associate-produced The Fight in the Fields, Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers’ Struggle, The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It, and AMERICAN MASTERS’ Ralph Ellison: An American Journey. Laurie majored in political theory at UC Berkeley and worked as an oral historian, focusing on the untold stories of women workers along the US-Mexico border. Her first connection to farmworkers was through her father, who volunteered at the UFW clinic in Delano during the 1960s grape strike.

6978 Views