By Monica Medina

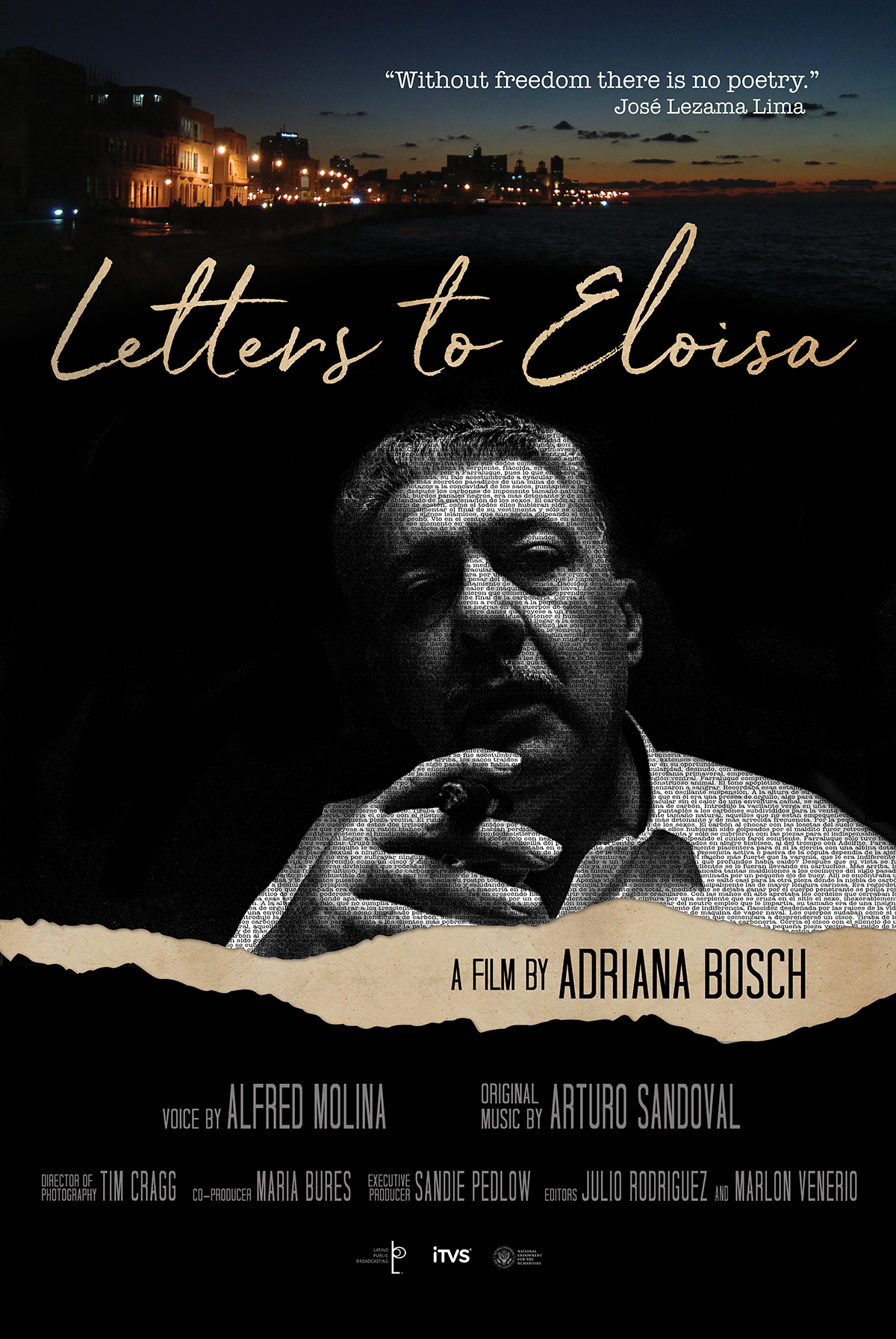

Adriana Bosch didn’t set out to make a documentary about Jóse Lezama Lima, the Cuban poet, author and philosopher. In fact, had it not been for a gift she received from a friend, around the time she completed a documentary on Fidel Castro, she may not have made the film at all.

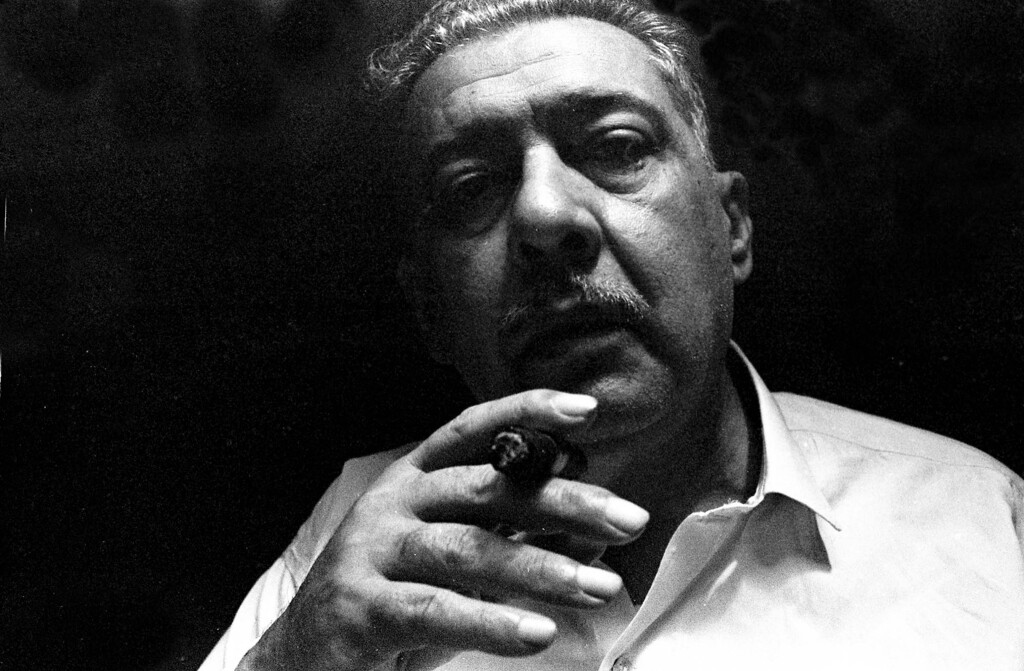

Jose Lezama Lima, Photo Credit: Ivan Canas

The gift was a book of correspondence the artist had written to his sister, Eloisa, after she emigrated to the United States in 1961. These letters were filled with the love and devotion that Lezama Lima felt for his sister. As Bosch, who has been an independent filmmaker for over 30 years, poured through the letters, Lezama Lima’s words resonated with her. In some way, they also haunted her, compelling her to make “Letters to Eloisa,” a documentary premiering on PBS as part of the acclaimed VOCES series.

“I had heard of him in the 1970s, when he published Paradiso, and though I had done my share of reading of the authors of the Latin American Boom, I was too distracted to dive into the novel’s 600 pages, but I did dabble into the first chapters which I found whimsical and mysterious. The letters revealed the experience of someone who decided to stay in Cuba to create literature within the Cuban Revolution; first thriving in the atmosphere of a cultural flourishing, and then struggling within growing constraints on artistic and sexual freedom. I honestly thought this was a holy grail for me, put in front of me as a beautiful gift.”

Paradiso Book Cover 1966. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Casa Museo Jose Lezama Lima

At the time, Bosch had completed a two-hour documentary on Fidel Castro, and was working on other projects, including serving as senior producer for two series, Latin Music USA (PBS, 2008) and later Latino Americans (PBS, 2013). Yet she spent some 15 years working on the film, writing one proposal after the next—including one submitted to Latino Public Broadcasting. She never gave up on telling Lezama Lima’s story, no matter what other projects were on her plate.

“The opportunity to tell any story through intimate correspondence is very rare for documentary filmmakers, especially those who work in history and biography,” she explains. “One of the most difficult things to draw out are the innermost feelings of our characters. That inner voice is so difficult to reach, but when you find siblings so close, and find a window into the soul of someone who was a poet, and who can express what is happening within him, well, you don’t turn your back on that.”

Shortly after launching Letters to Eloisa in 2006, Bosch came to realize how little is known about Lezama Lima. This was partially due to his unique style of poetry and prose, but also can be attributed to the Cuban government’s attempts to ensure obscurity for him and his work, despite Lezama Lima’s place as one of the great Latin American literary figures of the 20th century.

For the film, Bosch conducted extensive research, making repeated forays into Paradiso, and listening to and reading Lezama Lima’s poetry. She also spoke with and studied the work of many experts, and traveled to Cuba twice on research and production ventures, taking advantage of a thaw in US-Cuban relations under President Obama. Most of all, Bosch wanted to draw attention to Lezama Lima’s story in light of the progress—or lack thereof—toward freedom of expression on the island. While she found the progress against homophobia to be worthy of mention, she discovered that artists continue to come up against the boundaries of creative freedom. “Right now we have a dissident movement going on in Cuba. It’s never quiet and, except for the nearly absolute silence of the 1970s and into the 1990s, artists continue pushing the boundaries imposed by the government—those boundaries, which are never static.

“Beyond that,” continues Bosch, “I wanted to address the Latin American boom and the issue of family separation which relates to all Latinos in Latin America and the United States. On a larger scale, I always wish to make a strong statement against totalitarian government, and in favor of democracy and of personal and creative freedom.”

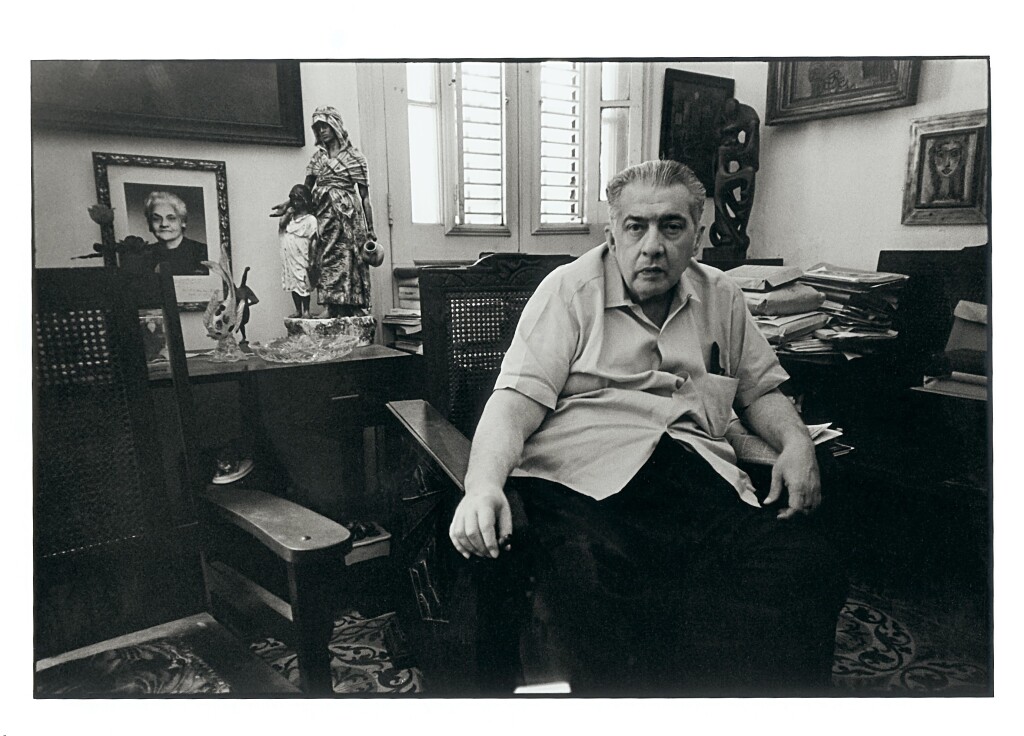

Cuban Intellectuals circa 1966

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Casa Museo Jose Lezama Lima

Bosch insists that at the heart of her film, remains the tragic love story of a brother and a sister separated by politics.

“Eloisa adored her brilliant older brother, who was her mentor and her teacher. When she first leaves Cuba in 1961 they don’t know whether they will ever see each other again. There was always a constant yearning. At first the letters ask ‘When are you going to return to Cuba?’ By the time he falls out of favor with the government, the letters begin to show the desperation of not being allowed to leave Cuba to see her again.”

Up until 1976, Cubans were prohibited from traveling to the United States. Additionally, Cuban Americans were not allowed to return to Cuba. Families were separated for 15 years, unable to see each other during that time.

“There’s a palpable tragedy there,” explains Bosch. “You look at the images of Cubans at the airport leaving in the 60s and it all seems exaggerated but in those days, particularly after the Missile Crisis in 1962, you never knew if or when you were going to see your loved ones again. Then when Lezama Lima becomes internationally famous after Paradiso, visiting Eloisa in the United States or Europe seems a real possibility but is denied to them, time and time again.”

Family of Jose Lezama Lima: From Left to right: Eloisa Lezama, José Lezama Lima, Rosa Lima, Rosita Lezama and Baldomera.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Orlando Alvarez Lezama

Encouraged by his mother to tell the family story, in 1966 Lezama Lima published Paradiso. Translated into several languages, it was a book he started working on in the 1940s. Essentially, it is the story of José Cemi, a character based on the author, and his life. The book explores his childhood, the death of his father, his upbringing, his homosexuality and his literary sensibilities. Paradiso is ambivalent about the political situation of the day and, as a result, became a highly controversial book in Cuba.

“Everyone says Paradiso is hard to read,” says Bosch. “The novel is a take on the history of this aristocratic family through the aesthetic excesses of the Latin American baroque and even magical realism, well before it became a movement. It’s also an intellectual and biographical coming of age story, weirdly erotic and sometimes even pornographic.”

In Lezama Lima’s day, homosexuality was not tolerated in Cuba. Bosch believes it is another reason why the Cuban government made Lezama Lima’s life so difficult, not allowing him to leave the country.

“Here is one of the most highly regarded writers in Cuba and he is not only the author of a book with heavy homoerotic content but he is not a revolutionary,” observes Bosch. She questions whether the government was afraid he would speak out of turn when he was away from Cuba, or make a joke or comment unfavorably about the revolution. Adds Bosch, “One of my favorite characters in the film, Professor Emilio Bejel, argues that the Cuban revolutionary government at the height of the official homophobia didn’t want him to represent the Cuban people.”

Jose Lezama Lima 1972

Photo Credit: Paolo Gasparini/ Courtesy of Fondo Urbano de Fotografia, Vzla.

When seeing the film, Bosch wants audiences to consider the lengths the Cuban government went to in order to break Lezama Lima’s spirit.

“He could have been far more influential if he had not been prohibited from speaking, publishing, and appearing in literary journals,” reflects Bosch. “At a time when Latin American novelists were becoming known, he wasn’t allowed to participate and be recognized. He died in 1976 and for his obituary he received a tiny column on the third page of the local paper.”

“A regrettable loss to Cuban letters.”

The English translation sums up the measures the revolutionary authorities in Cuba took to keep him down. Letters to Eloisa reflects on Lezama Lima’s final years in his homeland, locked up in a small home in the stifling heat and humidity of the Cuban summer, hardly ever venturing out, and barely writing any more or participating in the cultural life of his nation and the world.

“This is what happens when you silence people,” Bosch emphasizes. “When you take away people’s voices, and when you take away people’s choices and intellectual and creative freedom. There is an enormous personal cost to the people you take it from, but also a cost to society and the world, for it is deprived of the creative output of those people. That is really what this documentary is about.”

Adriana Bosch. Credit: Courtesy of Bosch and Company, Inc.

Bosch is grateful to the Latino Public Broadcasting (LPB) for airing her film as part of the long-running VOCES series.

“LPB is the perfect home for Letters to Eloisa. Like other VOCES documentaries, this is a story that empowers, informs and educates,” she says. “It also brings Latino stories into the PBS mainstream. The National Endowment for the Humanities also supported my film, but without Latino Public Broadcasting, this never would’ve happened. It shows just how invaluable is a series like VOCES.”

Letters to Eloisa is a film by Adriana Bosch. She is founder of her own production house, Bosch and Company, which specializes in documentary production and development.

Other core staff who contributed to the documentary, include: co-producer María Burés; editors Julio Rodríguez and Marlon Venerio; and associate producer, Laura López. For VOCES, Luis Ortiz is series producer; Sandie Viquez Pedlow is executive producer.

Bosch, who moved recently to Miami after 40 years living in Boston, likes to remind her audience that “films are made by their voices. In this case, I had access to people who were not only knowledgeable, but deeply passionate about Lezama Lima and his literature.”

Letters to Eloisa Movie Poster. Credit: Bosch and Company, Inc.

3208 Views